For several days now there has been a most annoying presence in my study. A draft of this newsletter - the latest in my Festivals series – has remained challengingly half written on my Mac. Every time I nudged the track pad, it stared me belligerently in the face reminding me that my 1st June deadline was approaching. Even when I turned off the desk lamp and thumped down the stairs, I could hear it whingeing fretfully about its parlous state of incompletion. Eventually, abandoned in an attic, it began to use bullyboy tactics. It banged on the floor above my bed and shouted that I needed to get my very poor act together and honour my deadlines. It called me a Pretender, an Emptyhead, a Slacker.

It's always more difficult to face down a nagger, a blistering critic, who doesn’t themselves have much to offer. One you don’t really like in the first place so who cares what they think? This half-baked essay, however, was actually very interesting, in the way that an old -style, tweedy, erudite, Cambridge Don with a life time of associations in his head and a teaching style of throwing them all out for you to follow up is interesting. But descriptions like that don’t always mean the same to a reader as they do to me, so let me just introduce you directly and see what you think of this poor stunted beginning of an essay.

At first it was moving very gracefully in the right direction. It started, stage centre, with Juneteenth, the American festival that commemorates the day on June 19th 1865 when 2,000 Union troops arrived in Texas. This was Confederate territory and although the Emancipation Bill had taken effect on 1st January 1863, this piece of paper had not yet taken effect in every corner of confederate controlled lands. It was only when the soldiers finally arrived in this westernmost part of Texas that more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state were finally actually freed.

From there the essay did a neat plié, lowering itself to the recognition that slavery still exists in modern days and that the effect of original slavery still resonates, before making a lightfooted jeté sideways to the city of Liverpool where most of my legal practice took place. There, surrounded by streets named after slave owners and abolitionists stands the National Slavery Museum.

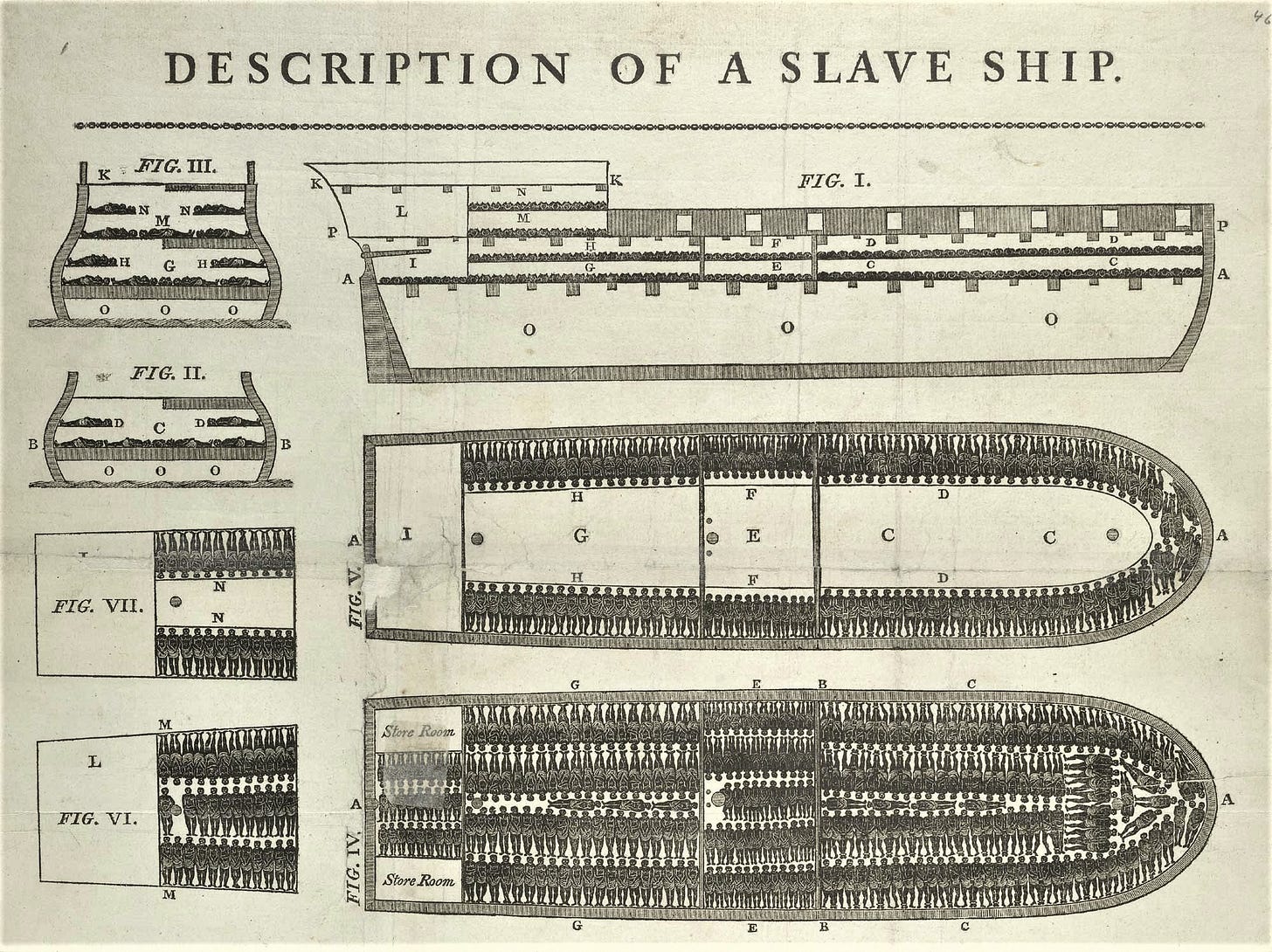

It was from the docks outside this old warehouse building that the Brooks set sail, the ship whose infamous plan illustrated the horrors of the Middle Passage journeys in a way that words could not.

IMAGE: PLAN OF THE SLAVE SHIP THE BROOKS

It was from here that the Kitty’s Amelia, the UK’s last slaving ship set sail on 27th July 1807. In fact the Act that abolished the slave trade in the UK passed Parliament in March 1807 and took effect on 1st May, a full 58 days before Hugh Crow took the ship up the Mersey, all the way to Sierra Leone and from there, laden with 233 captives and, proceeding under the protection of a Royal Navy sixteen gun sloop, headed to Barbados. The post abolition sailing was legal because the bill of sailing had been signed on 27th July 1807.

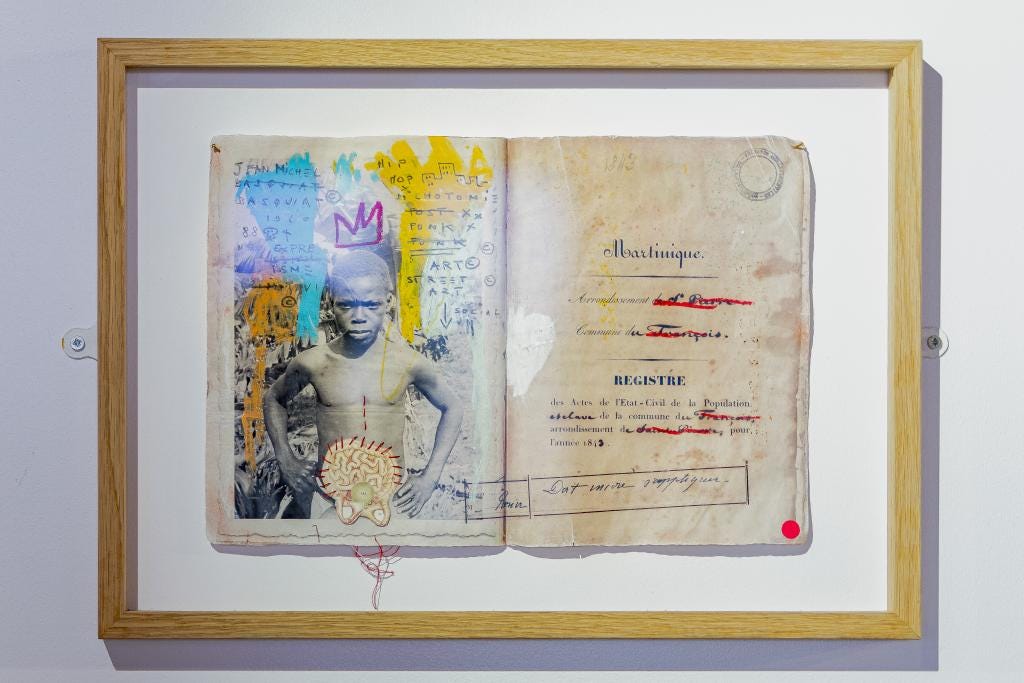

With a fancy chassé the essay then seamlessly glided through the front doors of the Museum down to the far end where the art work Lambeaux (Scraps) by Gilles Eli-Dit-Cosaque hangs. These six pieces are an imagined diary, using photographs and annotation in the form of a deconstructed journal, each frame holding a two page spread with a binding fold down the middle. It is described as making reference to the process of creolisation not in a geographical sense but as a state of mind.